So many pieces, so little time.

An awful lot of points of national survival converge from this little misstep by Nike in re the Matter of Colin Kaepernick as their new #JustDoIt poster boy.

The first piece of the jigsaw is why do so many corporations these days get away with throwing their “brand” and potential profit margins under the bus, when both are treasures their boards of directors and management in publically-traded companies are required to protect? By law?

Nike took a five point tumble when they launched the new Kaepernick campaign a few days ago, but have gained much of it back. And sales have increased, so any notion that Nike may lose money long term is premature to call. In fact, overseas, where America (and Trump) is seen as an enemy to European political and ruling class anyway, Nike’s stock may go up.

Brand analysts are guarded about the long term risk Nike has taken, and may profit from it, since most of Nike’s buyer-base are high-end spenders who are largely indifferent to patriotic themes, National Anthem and such, but virulently opposed to ideas that are sold to them as racist.

I’m most taken by the notion that Madison Avenue largely sees America as little more than a “brand” that can be bought and sold.

Hold that thought, for in the up-scale buying market, everything, including ideas, have to be sold. They are rarely learned or discovered anymore, either from intellectual inquiry or by personal observation.

Brand analysts know this, even if most of us don’t. And they’ve known it for a long time. And their best paying jobs are in politics, not in selling retail products.

In the Kaepernick case, it’s almost as if some market guru came to Colin three years ago and said, “Since your career’s not going anywhere anyway, let us pitch this idea.” Maybe they even sent in the succubus.

Don’t laugh, this is perfectly plausible.

So in a related story, people thought Dick’s Sporting Goods would suffer when they distanced themselves from the NRA brand after the Parkland shootings in February. But they had actually stopped selling assault-style rifles long before, in all but a few subsidiary stores, after Sandy Hook in 2012. Dick’s is down over 10 points since Sandy Hook (close to 25%) but up about 5 since Parkland (2017), so the retail chain’s financial condition may have little to do with the NRA or its 2nd Amendment position.

While publically traded, Dick’s is still a family company and its brand loyalty is nothing compared to the iconic name of Nike and its swoosh.

But Dick’s sells Nike, so we’ll see as the NFL season progresses if they can dodge a second round of outrage from an even broader audience.

Dick’s target audience is also up-scale. You don’t go there to find $4.99 sweat shirts except in the Close-Out bin. Dick’s buyers look for brands that represent a certain element of prestige and exclusivity; top floor products like Nike.

In Dick’s line of sporting goods the brand or label (on the outside of the garment or tent, or boots) are apt to be more important to buyers than function. We know this because brand analysts tell us this is so. They are not trained to know or understand the intrinsic nature of any product.

That’s why that label or logo is so prominently displayed. The Nike swoosh is iconic, selling Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods gear for over 20 years at top-dollar prices.

It may surprise you at how top-dollar.

Did you know that there are $30,000 Nike shoes? The question is: where is hidden the additional $29,900 that separates those shoes from a $100 pair of Nikes at a shoe store? Or even a $60 pair of low-end Nikes? Labor costs? Do they have special production units, paying much higher wages, maybe even up to two bucks an hour? What about the cost of the pieces? Short of woven gold (which can be done, btw) no 3 ounces of fabric or leather is worth $30,000. Then there’s design R&D, and it’s true Nike does spend extra R&D in developing special shoe design for comfort. But their shoes are not “engineered” in the same way a BMW is engineered. Don’t confuse the two.

Still, Nike products are not off-the-rack, or their buyers wouldn’t get close to them.

So the vast amount of “production costs” of most name-brand athletic wear is in marketing, in establishing the logo/brand as a desirable product to own. Shoe companies vie with one another to be able to land star athletes to pitch their products, at the cost of millions. And they give away thousands of pairs of shoes to athletic programs just so people in the bleachers will identify Nike or Adidas with their favorite sports teams and stars.

But unlike Big Pharma, who justifies high costs for drugs to recover the failed development costs of pills that didn’t make it onto the market, Nike’s actual cost can generally be tagged with every pair of shoes. They don’t (or shouldn’t) have high development losses.

In other words, people will pay $100 for a $30 pair of sneakers, which cost less than $2 to make, just for that Swoosh.

But about that label.

I was in the outdoor business in the 80s, in outfitting, field testing and production of outerwear and gear, while a manager in a textile manufacturing company. I had yarn, knitting, cut-and-sew, and laboratories at my disposal. And it was an exciting era, when clothing and equipment quality actually mattered more, because in those years of our lives, we pushed things to the limit. Boomers were actually wearing gear that had to be effective at sub-zero temps. We had to have boots whose welts would not separate on 200-mile alpine hikes.

All the great brand names of outdoor gear today were in their infancy then, (except for LL Bean). I watched them grow from pups. That was my passion. And that label was the byword for their quality.

Nike was still a gym shoe then, and not among them.

I had a newspaper editor-climbing friend who believed Patagonia made the best outerwear in the world, but hated the iconography of the way they placed their labels, so ripped everyone of his off.

I kept mine on, giving my last piece of Patagonia headgear to the manager of a lodge on Malovitza, an ice-climbing mountain in Bulgaria. It was the last mountain I’d ever climb. The manager there had lost his wife and four toes on K12 in the Himalayas and Bulgaria gave him this job as compensation. He gave me that blue rag he’s wearing in the photo. (Priceless.)

But Patagonia didn’t make this ball cap. Only the label.

Every famous brand sells its label or logo for a variety of products, tee-shirts, sweats, caps, but has no involvement in the manufacture of those products.

You already know this. This cap, with a different label, would sell at Bill’s Farm Supply for $4.99, and at a chic store in LA, or maybe even Dick’s for $12.99- $18.99. Whatever the market will bear. Label determines.

I laughed at my newspaper friend at the time, but he had a point, for as my Boomer generation got older, and we did more family outdoor things versus humping trails 15 miles a day with fifty pounds on our backs, our passion for the sweat equity we put into the quality of outdoor gear changed.

Even though their numbers have quintupled since the 80s, far fewer upper middle class white-collar managers would spend a week on the trail to the Mountains of the Moon in east Africa, or even the 72-mile stretch of the Appalachian Trail in the Smoky Mountains. They are much more sedentary.

But they still like the labels that suggest they are not. And the sales people at Dick’s know it. Manliness and adventure are marketed and sold the same way sex is.

The better brands have spread out to other kinds of outdoor products, for the whole family, but still project that original base of solid, survival-quality even though those products are rarely called upon to perform at that high level. I haven’t slept on zero-degree hard ground in 30 years, but still brag that my REI sleeping back cold handle it, “if I wanted to.”

This is where the generational passing of the management torch within a corporation is important, for it would be reasonable to expect that some in the marketing side of the house could find a lot of extra profit to be found in a lot of unused or “unneeded” cost ofquality, once a label seems to be able to sell itself.

The bottom line is that once a brand is “made”, you can cut quality-parameters in half and the buyers won’t know the difference. In my Army days in Japan US soldiers gathered up empty scotch and brandy bottles and sold them to bars off post who would fill them with Japanese rot-gut, knowing the Japanese buyers would never know the difference and pay $20 a shot for just that label on the bottle.

So, this concept is ancient, and good companies who still “own” their brand will go to great lengths to protect it from corruption. Brand managers don’t see things that way, and are likely taught this while pursuing their MBA..

Called “plucking the golden goose clean”, still, this is a common practice in many third-and-fourth generation companies, especially if the founding family is not involved in its management anymore.

Some household names just die, as has been occurring in the American economy since RCA Victor, Kelvinator and Chase and Sanborn were household names, all far better known in America than Patagonia or North Face are. Part of a natural cycle.

But the ideal of America is that they are replaced by a better product, not a better-presented or better-marketed product.

Nature only favors one of those alternatives.

My opening question was what happens when the corporate culture behind the brand no longer has to abide by the “natural laws” of business survival?

Delta Airlines also took a big hit when the State of Georgia cancelled a tax break over their disaffiliation with the NRA. CITI bank also was hit when they refused to accept credit card charges from gun retailers. How this will play out in the board rooms is still unknown.

And then there’s the NFL (and ESPN), which brings us back to Kaepernick and Nike, for they seem to be doubling down on the Anthem issue, by choosing a bunch of millionaire athletes over millions of fans who’ve made them rich over the past 30-40 years. (Ray Nitschke did not retire rich, as Colin Kaepernick is now, without having to play. I doubt if Pete Rozell retired as rich as the entire front office in the NFL seems to be now.)

Have they actually put the NFL brand at risk, or have they simply decided to go a different way with a sport and fan-base that may be dying out anyway, with a dubious future of lawsuits; as I said, just plucking the goose clean while it still has feathers?

Some suggest they are ignoring patriotic Americans, who, if you analyze the Trump voter base, are largely white, largely without college degrees, and largely over 50, so won’t matter in a few years as a target demographic. Major brand managers wrote us off years ago, except maybe drug and insurance companies..

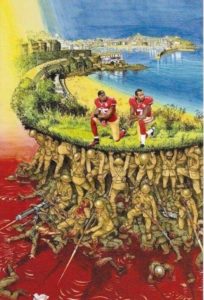

Yes, they are missing something here. This is it, here.

(I’d like to credit this art, so if you know, let me know.)

The first question I want to ask here is what has really changed in corporate-boardroom thinking since Nike was just a pup?

And ancillarily, why has an entire brigade of political observers totally missed it? Could it be that all that history I just quoted, about the brands they know today, from the 1980s, which occurred in their childhood, is totally beyond their ken?

Are these questions they do not know to ask, or they think are irrelevant?

Or is it something else altogether?

Hollywood deletes the American flag out of the most iconic moment of JFK’s dream for America to conquer space, where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin plant the American flag on the moon. How do the film’s investor’s feel when no one over 50 shows up to see it because of that omission, and no one under 50 thinks it’s important in the first place?

Is this where there is a convergence between the next NFL generation, who doesn’t know what the National Anthem means and the generation who never really bothered to learn that once upon a time man couldn’t just fly off into to space and land on other planets, so it was a big deal when he did?

Any product’s name and reputation can be destroyed by outside forces having nothing to do with the product once the intangibles of that product have been reduced to becoming a mere “brand”, a name bought and sold on the trading room floor, or worse, be caused to trend on Twitter.

That the American version of capitalism is possibly being cynically erased by Madison Avenue via America’s business schools should be a thing we need to pause to consider.

But if it is being done intentionally, in favor of a higher form of corporate management that favors one class of manager over all others, we need to do more than just pause.

1) Considering the change in the corporate world in the 80s, which produced Skillings and Fastow (Enron) in the 90s, alongside the corporate environment that allowed Jesse Jackson to shake many of them down on the fear of appearances alone, how easy can this be morphed into a corporatist world-view of government that is survival-endangering to a free peoples…as we have known that to mean?

What are the moving parts?

And 2) how has all this has been missed by a generation of political-social observers who seem unaware of the importance of events that shaped the lives of their own families and the shoulders they stand on, whether they’d been here ten generations, or just one?

I get the sense these may be outcome determinative in assessing what lay ahead.

These are two turns in the road I want to explore, if for other reason than to make a record that the question was at least asked.

Stay tuned.

[…] Vassar Bushmills […]