Another in a series about common people I wish you could have known.

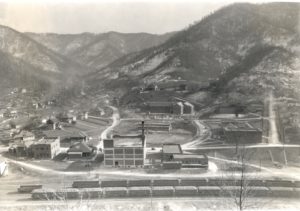

I was born in a small town of just over a thousand people. It was a company town that ran the length of a creek that hugged a huge mountain, for most of a mile. The entire town was on one side of the creek, the streets all running perpendicular to the creek. Like bureaucracies, law firms, and corporate offices, you knew who was who just by where everyone lived.

There were only five professional managers; the general manager who lived in a “palace” at the top of a hill; gated entrance, kitchen help, gardener, and just below him, outside the gate, the chief engineer, then the second engineer, then below him the chief accountant, and bookkeeper-paymaster…plus better homes for two doctors, both Harvard men from the FDR era. Flanking this one street beneath the big house on the hill were three more streets of salaried foremen, all according to rank and seniority, then, as you went to the end of town and far up into the hollows…one street ran straight up half a mile…the newer employees lived. All of their kids walked to school every day. I walked thirty yards.

I was raised in a broken home, sort of, since my dad was one of those engineers. So we lived near the top of that hill. My mother, on the other hand, had dropped out of school in 10th grade, and they had different ideas about entitlement and about raising their children. Especially the oldest son. Me.

My mother believed, being “management” that she could enjoy the perquisites of the title, and that her children shouldn’t have to suffer the ordinary rites of passage others’ kids did. Mother wanted it known that my dad’s name was stenciled on my forehead in invisible ink and anyone who messed with my hair would have hell to pay from on high. If I came home with dirty clothes from fighting…which in first grade was almost daily…not only did I get a tarring but the other kid’s mom got a phone call, or my dad got an earful when he came home for supper. Mom was a real storm trooper about “privilege”. Piano lessons were even involved.

My dad on the other hand had come up hard, having been raised in the back alleys of that very town, his father an ordinary coal miner, and only after having been recognized as having engineering skills after three years in North Africa and Italy, was sent to school by the Company to become an engineer. It was the only job he ever had his entire life. And he finally ended up in that big house on the hill. But he wanted his kids, me especially, to learn certain rules of manhood.

So, while Mom whomped me if I fought, Dad whomped me if he ever heard I’d walked away from a fight. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. Other mothers were in on this conspiracy as once I remember Gary Lewis and I once stripped down to our skivvies to duke it out, just so as not to get whipped for letting our clothes get dirty.

So for a few years, into fifth grade, it was dodge ball with Mom and Dad.

Then came Mick Hensley.

When I was in fifth grade Mick was placed in my class. He was 14 or 15, while most of us were 11, head and shoulders bigger than anyone else. Mick was like a lot of big roughneck kids then, he was still too young for Shop, and had no interest in anything they taught in school, and only wanted to wait until he turned 16 so he could go to work in the mines. (In those days, school teachers earned about 3,000/yr while miners earned closer to 5,000.)

My mother immediately tagged Mick as a thug and a bully. She knew the family, way, way up Machine Shop Hollow. Kept pigs underneath the porch. Never came to church. Kids, all eight of them, always looked like they needed a bath. Heathens!

In truth, since we grew up side by side for a few years, Mick was as gentle as Dan Haggerty, just real rough around the edges. A true nature’s child, he ran the hills like a goat, barefoot as often as not, held the record for typhoid shots I guess, from rusty nails and barbed wire. He built a cabin from saplings and binder’s twine (I used to camp in it when it rained.) Long shocks of red hair, freckles all over his body, and a big grin, a genuine Huck Finn…who coulda played fullback for Notre Dame.

Most of all, Mick had a native, uncultured sense of honor, honesty, and integrity that no kid could learn in Sunday School. On weekends we’d all meet behind the school and play Cowboys and Indians, or somesuch, dividing up into two “armies” usually of 8-10 each. And for guns we’d use sticks we’d find on the ground, that curved just enough to give the stick, and us, some class.

One of those days I ran smack dab into Mick’s sense of justice. We were running and diving behind corners of building, trees, big bushes, going “Bang bang, Gotcha”, when I was running one way and all of a sudden Mick stepped from behind a bush. I jumped behind a half-inch poplar sapling which wouldn’t have concealed my left hand, just as Mick yelled “Bang, Gotcha”. I yelled, “No, I was behind…” only before I could finish my defense, I was trying to pick myself up off the ground, my nose wrapped around my right ear, blood gushing all over a fairly new shirt that Mom told me not to get dirty.

Mick just bent over, with a big “ah shucks’ grin and helped me up, and said “Y’ought never lie” as if he was telling me to zip my fly. I’d never even thought a cuss word before, but a big “Oh, hell!” just shot through my mind as i looked at my shirt. What will Mom do? One of the other guys had a handkerchief, which I used to staunch the bleeding, then I walked that long march home, never reflecting on the lesson of the day for many years to come.

Most people learn these lessons quickly. One bloody nose usually does it. I never knew I was law school material until Mick had to teach me again, a year later, up in the mountains, during an acorn fight. Thrice broken (football), I had to have most of the cartilage surgically removed so i could breathe, but from that day forward, every time a lie comes rushing to the tip of my tongue, like a fellow who ducks walking under helicopter blades, i just naturally flinch…and the lie retreats. Even today.

It was in this mangled state that I entered law school in 1968, only to realize that not one other of those students had been initiated into the secret rites of truth as I had. I knew stuff they didn’t know, news they could use, and as it turned out, would likely never learn. It was then I first appreciated Mick Hensley.

Mike Hensley had an irresolute respect for truth. Actually a lot more, I learned, as he stayed in town well after I’d moved onto college. Like Franklin, he believed the greatest deterrence to crime (sin) wasn’t the severity of the punishment, but the absolute certainty of it. Pretty damned swift, too. Two tries, I still never got to finish my final argument to jury either time.

So I’ve always been in his debt. Merely thanking him isn’t enough. I’ve always wondered what happened to him. He moved away while I was in college, took a job in the Ford plant in Cincinnati, married I guess, children…never knowing he’d saved a life…and I mean this as deeply as I can mean anything…

…or that I had saved his, for when I went home that night, my new shirt all bloody, my mother demanded to know what had happened. I told her I fell. Had she known Mick had cold-cocked me, he’d have been in reform school within a month. And Polly’s boy would have been the whiniest snitch in town.

Sometimes, in the smallest of things, we can all see how civilizations, and enterprises, can rise and fall.

I think about Mick from time time because as the years passed I thought of all the genuinely fine minds that passed through America’s law schools, business schools, and colleges, Bill Clinton comes to mind, that were just one bloody nose away from being men. So sad.

Mick Hensley was one common man I wish a lot of you could have known. Maybe you had one too. I hope so. I sure am blessed, I know that, for sure.

America would be a much better…and safer…place now if we had more of them.

This too, is why we fight.